Floral motif Victorian era silver topped gold brooch, en tremblant, set with old mine and rose cut diamonds, converts to hair ornament, French assay marks, infitted case by Henri Blanc Paris. Courtesy, Gorky Antiquites.

Purchasing antique jewelry is a bit like going on a treasure hunt. Each piece is a little bit different, you never know what you’re going to find and of course you’ll know it when you see it. Once you find “the one” you want to be sure that the piece is what it is represented to be, that it is in fact a true antique jewel — which for the purposes of this blog is defined as through the late Victorian period — and not a reproduction.

The first thing you want to do is start by working with a reputable jewelry dealer or retailer. Always ask for any gemological reports and other paperwork that may help to authenticate a piece. While it takes an expert to verify the authenticity of an item, every jewel will give you clues to its background. First you have to know what to look for and then it’s a lot like playing detective. Careful examination of a piece of jewelry from all angles is necessary. If you’re buying a very expensive or exceptionally rare piece of jewelry, then you may want to have it reviewed by a third-party, such as an appraiser, who does not have an interest in the sale of the jewel.

To help you get started in determining if a piece is worthy of a second opinion, Gail Brett Levine, GG, executive director of the National Association of Jewelry Appraisers (NAJA) offers ten tips for determining if a piece of jewelry is actually an antique. “If you want to find out more about a piece, go to an appraiser who has a jewelry history background,” she advises.

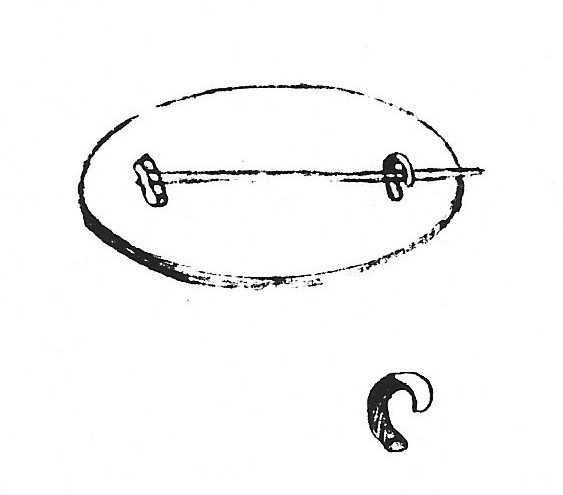

• A reproduction will normally have modern safety clasps and will not have handmade pin stem and joint tube hinges unless designed to defraud. “In an antique brooch the pin stem will be considerably longer than the catch,” explains Levine. “The pin will go one-quarter to three eights of an inch over the outline of the brooch. These early clasps were C clasps with no safety catch. The extra length on the pin was there to catch the fabric so the brooch would be held in place more securely.”

• Look at the prongs on a piece for more clues as to its age. In old pieces prongs will be worn smooth. In a reproduction piece the prongs will be large, a bit chubby, and they will show no wear.

• Hinges on a reproduction bracelet will be “wiggly” and heavy. The snap will generally be a “two piece solder” rather than a one-piece bent over snap.

• The backings of reproduction earrings will be post and friction nut style rather than post and screw nut style. In newly made pieces the post is smooth and the back, or nut, will slide right on to the post. In an antique piece, the nut or post will sometimes have threads, similar to a screw, and the nut will screw onto the post back.

• Threaded areas should show wear and tear in antique jewelry. “With repeated wear the threading on the nut will wear out. The hole in the nut will become enlarged and it doesn’t hold well anymore,” says Levine.

• There were no cultured pearls before approximately 1910. Additionally, cultured pearls were not widely available until the 1920s. The only way to determine if a pearl is natural or cultured is to have it examined by a gemological laboratory. Older pieces will have handset pearls, where the post is fashioned to fit the drill hole of the pearl, rather than glued pearls.

• Reproduction chains do not show the wear and tear that old chains will show. “The links, especially larger links like you will see in Georgian era jewelry will show indentations in the metal from wear,” comments Levine. “The links on pieces that were worn a lot will rub against each other and you will be able to see an indentation that looks a like a woman’s hourglass figure.”

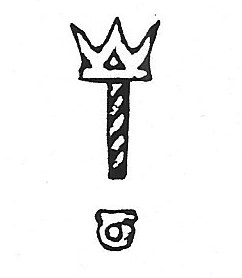

• In a modern piece you will often find the metal karatage stamped on or near the clasp. The clasps are generally finely made and they will have a tongue that fits into a groove to open and close the jewel. “On antique pieces the clasp is often bulky and thick,” says Levine. “For the most part if a piece of gold jewelry is stamped 18-karat it is European, if it is stamped 15-karat it was made in Britain, 15-karat gold is no longer made so that is an indicator of age. It was also possible to find 9-karat gold, or silver topped gold that made the gems shine more brightly.”

• Make sure that the gemstones — type and cut — and materials are typical of the period and style represented. Various gemstones were discovered at different points in time and some gems were not discovered until the 20th century — for example, there is no tanzanite in antique jewelry. “A good rule of thumb is that generally a sharp cornered or step cut stone will not be in an antique piece,” says Levine. “The technology for that type of cut did not exist at that time. If the piece has sharp corners it does not belong. You start seeing those angular cuts in jewelry starting in the 1920s.”

• Stamped markings for gold karatage will be too crisp and clean in a reproduction, but may be somewhat worn away in an older piece.

Every piece of jewelry has a story to tell — including its own history. A careful examination of a jewel will tell you much about it, from whether or not it has been repaired, is a reproduction or even its approximate age.

Authored by Amber Michelle