By Olivier Bachet

Since the dawn of mankind, man has been making jewellery from shells, amber and teeth. Amulets, liturgical figurines as well as grips on spears were sculpted in natural materials for which man had easy access. Inspired by these ancient human traditions, Cartier introduced a certain number of natural materials originating from the worlds of flora and fauna into the making of their jewellery and objects which they offered to their clientele. We shall describe different articles the main elements which were used and for which their use has been known since the beginning of time bearing in mind that Cartier has used throughout its history, elements which few people could even imagine being used in the making of an art object, such as a carved, openwork stork’s beak which covered the extremities of a vanity case made in Paris in 1926.

Ivory

All civilisations have drawn upon ivory to make objects which have been both practical as well as decorative. It comes from mammal tusks. It can be assumed that the ivory used by Cartier comes from elephant tusks even though it is possible that some ivory came from other species such as narwhal, hippopotamus, walrus and even boar.

Love Birds, Cartier-Paris, circa 1907

Ivory, agate, fluorite, rose quartz (Courtesy of Palais Royal)

Desk clock, Cartier-Paris, 1911

Ivory, gold, enamel (Courtesy of Palais Royal)

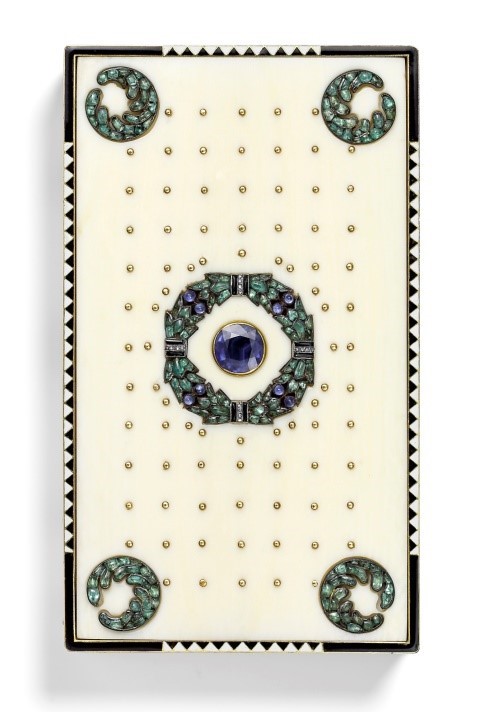

Nècessaire, Cartier-Paris, 1927

Ivory, gold, emerald, sapphire (Courtesy of Cartier © Photo Nills Hermmann)

During the Belle Epoque, ivory was not rare and its use was diversified and widespread. Cartier used it mainly for secondary elements, that is, for elements on the inside or elements which were hidden including for example, the supporting plaques of dance cards or beneath an object such as table bells. In this case, the ivory plaque was stamped with Cartier’s signature using delicate cursive letters as well as the inventory number of the piece.

Easy to sculpt, ivory was also used to make more visible and elaborate elements such as the perches for lovebirds, owls and parakeets. Easy to dye, Cartier also used it to create the branches on a Japanese cherry tree in 1907.

When the size of the tusks or the teeth allowed, the goldsmith didn’t hesitate to make pieces whereby ivory was the principal material. In 1910 and 1912, including those with a folding strut, many round, square and arched desk clock models were made in ivory.

Sudanese bracelet, Cartier-Paris, circa 1919

Ivory, gold, enamel, onyx (Courtesy of Artcurial)

“Rose” brooch, Cartier-Paris, 1965

Ivory, gold, ruby, diamond (Courtesy of Palais Royal)

In the 1920s, the use of ivory in the manufacture of objects became more restrained. Some pieces continued to be made in ivory as its whiteness allowed for bold contrasts with enamel or coloured gemstones as was found on a vanity case from 1927 which was decorated with sapphires and emeralds. However, at the time, this did not represent most of the production at rue de la Paix. On the contrary, the use of ivory in the manufacture of jewellery was increasing. In 1919, Cartier began to produce the famous « Sudanese » bracelets, directly inspired by traditional African jewellery. The body of these bracelets was most often made of ivory with some enamelled motifs and the ends in coral, jade or onyx. An organic porous material, ivory is sensitive to dehydration. Fragile, it can crack with time and its beautiful cream color tends to yellow.

The development of synthetic materials such as bakelite, galalith and ebonite creating the illusion of ivory meant that these new materials could replace ivory. This was the case for the ivory casing of a Chinese desk clock which was replaced in the Cartier workshops by an ebonite casing which was more resistant to the ravages of time. After the Second World War, the use of white chalcedony, both resistant and easy to obtain, was frequently used in the manufacture of jewellery and tends to replace ivory. It is only in the 1960s that we find again pieces made of ivory. Its ease to be carved allows for example to perfectly render the delicate petals of white roses which, mounted on a brooch, will meet a great success. Since the end of the 1990s, awareness of the fragility of nature and the desire to protect wildlife has imposed a total ban on ivory. It is a safe bet that Cartier, like other great jewellers, will never again use ivory in its creations.