WRITTEN BY CLAUDINE SEROUSSI BRETAGNE @ARTOFTHEJEWEL

Over the years there have been many books written about Cartier and Van Cleef & Arpels, exhibitions too. Books about modernist jewellers such as Jean Després and Raymond Templier and important survey books of the Art Deco period. When it comes to Mauboussin, aside from Marguerite de Cerval’s excellent 1992 monograph on the firm, and a handful of dedicated chapters in other publications not much attention has been given to the venerable house. This article is not an attempt to re-write Mauboussin’s history, but rather shed some further light on one of the dynamic forces that led to the firm’s success in the inter-war years: Pierre Georges Yvon Mauboussin.

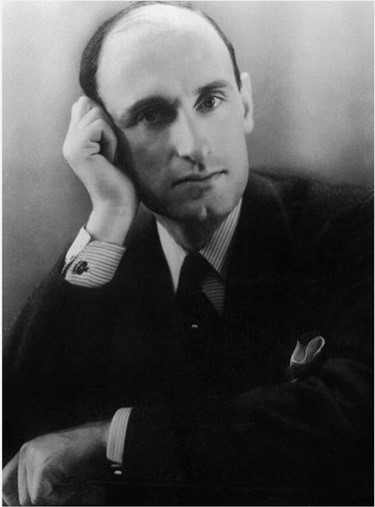

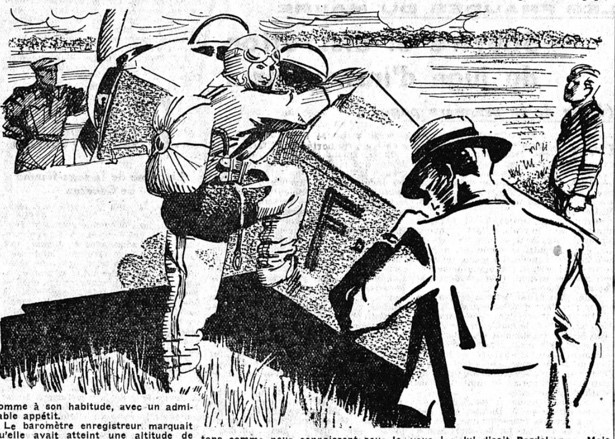

Fig. 2 Mauboussin (in a hat) with his chief test pilot, and a great friend, Léon Bourrieau c. 1950s

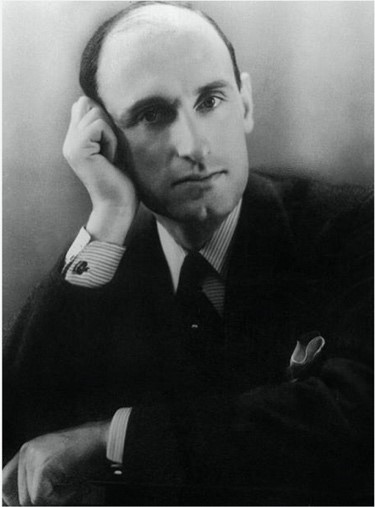

Born in 1900. One of three children, and the only son of Georges Mauboussin, like many of his contemporaries (Jean Fouquet, Gérard Sandoz, Raymond Templier, André Rivaud et al.) he was born into a multi-generational jewellery business. Most portraits of Pierre from the 1920s and 30s show a sombre and pensive man (fig.1) and it is easy to form a quick opinion from these portraits. But he was by all accounts affable, charming, cultured, modest, debonair, amusing, highly intelligent, absent minded in the way only a professor could be and a natty dresser. A photo of him taken with his test pilot Léon Bourrieau (fig. 2) in the 1950s gives a better sense of the man. Pierre remains a fascinating creature. Unquestionably loyal and passionate about the family firm as well as possessing a great commercial mind, excellent taste, and a passion for art and design. However, his great love, was aeroplanes – a passion he shared with his father. Through much of the 1920s and early 30s he managed to nurture both, side by side, before fully committing to his airplane business by 1940. His interests and his character informed the identity of Mauboussin and the nature of its output.

It is hard to be certain of what sort of father Georges was, but father and son seemed to have a good relationship that was, amongst other things, forged around shared interests: cars, planes and, in George’s case, bicycles. For Georges these were passions and hobbies, for Pierre these were obsessions that were to shape his path in life. Pierre, like André Rivaud, went to university before joining the family business. In Pierre’s case he graduated from HEC (École des Hautes Études Commerciales de Paris) the top business school in France, rather than an engineering school as some have written, and promptly joined his father at the firm in 1923-4. It is at this point that Mauboussin seems to begin to flourish. Rather than it being solely as a result of Pierre’s efforts, it seems down to the perfect alchemy that the partnership between Georges (the face of the company), Pierre and Marcel Goulet (George’s cousin and the commercial mind) created when Pierre joined the firm.

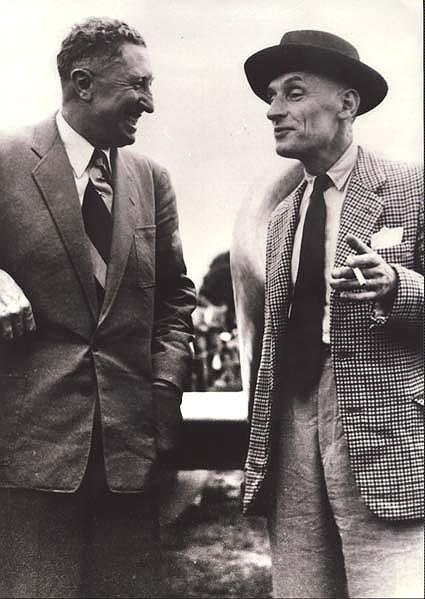

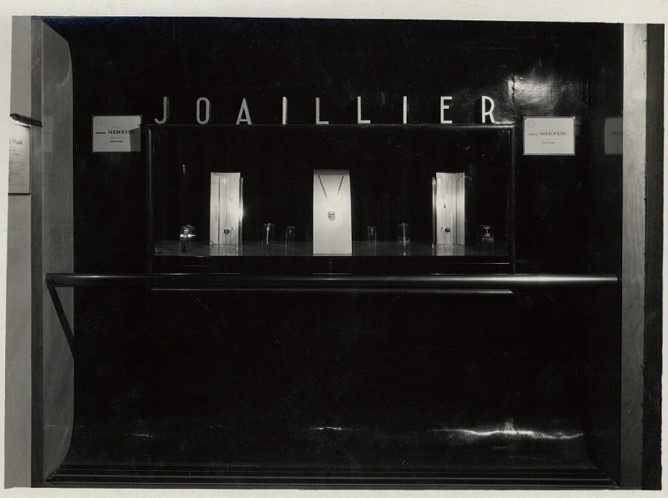

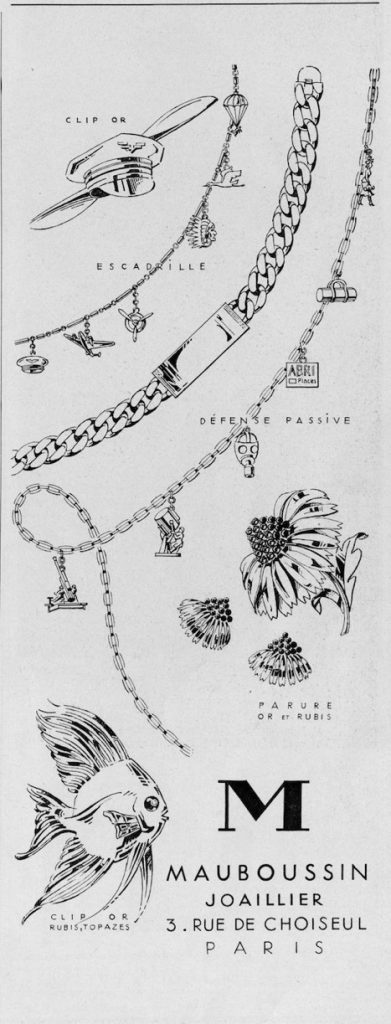

Mauboussin, during the interwar years – at the very least until 1935 – was an odd fish in an utterly compelling way. It had the appearance and the polish of a Place Vendome jeweller, yet it embraced its wholesale roots. George’s decision to establish Mauboussin’s headquarters and flagship store at 3 rue de Choiseul (fig. 3) was telling. Although a hop skip and a jump away from Rue de la Paix, it remained amongst the workshops and stone dealers. As a firm it was technically and commercially innovative and yet had a solid business sense appealing to a varied client base. They were a wholesaler, a stone dealer, which they happily advertised unlike their contemporaries, as well as having their own, sizeable, in-house workshop and stone cutting enterprise. They were also a retail jeweller, which is what they are remembered for today.

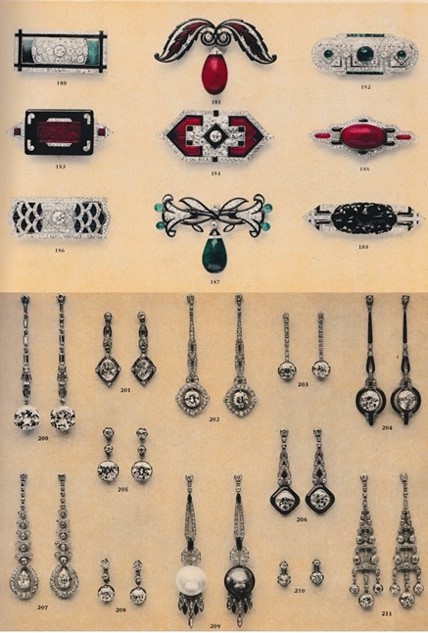

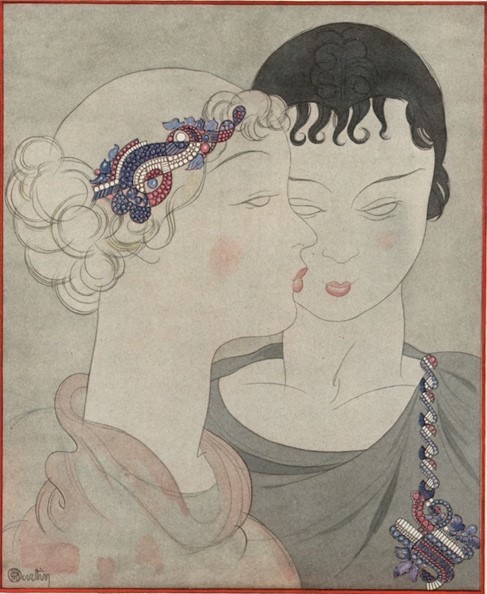

Fig. 4 Pages from the Mauboussin retail catalogue, 1923

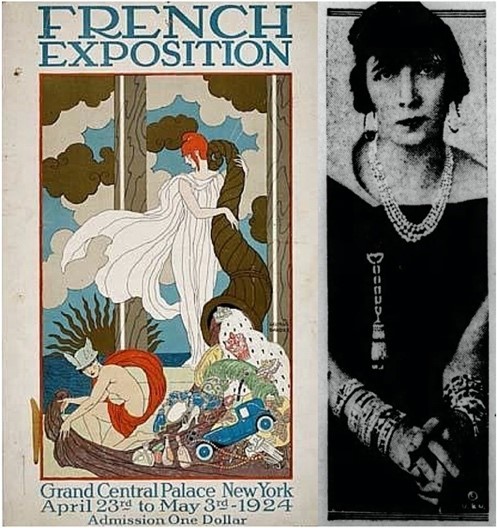

Fig. 5 Poster for the 1924 French Exposition and a photograph from the American press of a woman bedecked in some of jewels that Mauboussin exhibited in New York

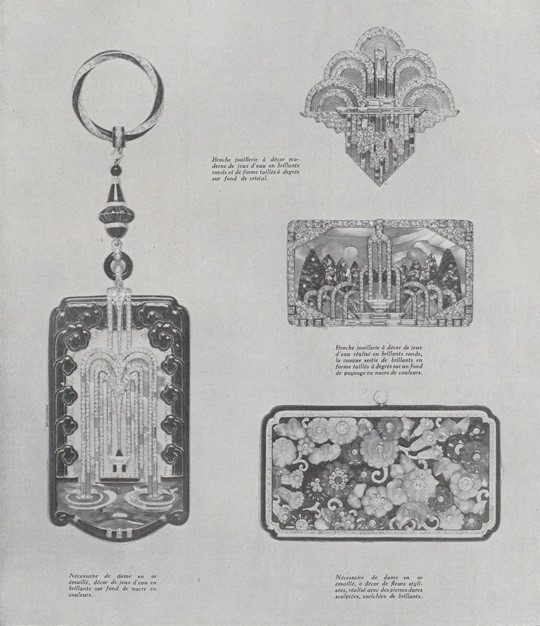

Fig. 6 Mauboussin jewels from the 1925 Exposition des Arts Decoratifs in Paris

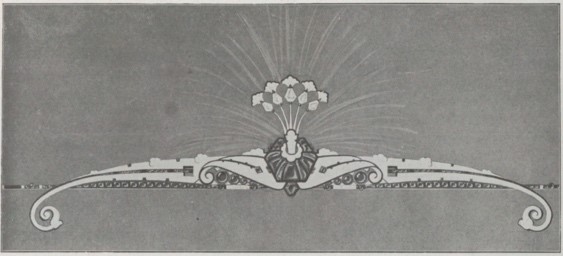

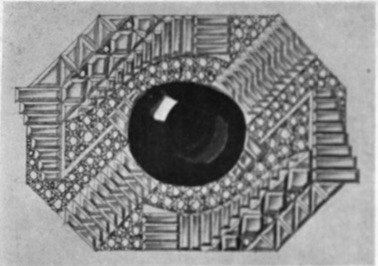

Fig. 7 Maurice Valley’s 1924 prize winning design

As one can see by their first catalogue in 1923, they made very beautiful early Art Deco pieces, very much in fashion but it was nothing ground-breaking (fig. 4). Pierre’s first independent project was to head to New York in 1924 and establish an office there as well as represent the firm at the French Exhibition (fig. 5). The jewels exhibited proved to be a great success and brought Mauboussin into the consciousness of American society through the considerable press coverage they received. This exhibition in New York along with the 1924 exposition in Strasbourg was to bring Mauboussin increased recognition and enabled the firm to spread its tendrils further across the Atlantic (adding to its established representative offices in Rio de Janiero and Buenos Aires).

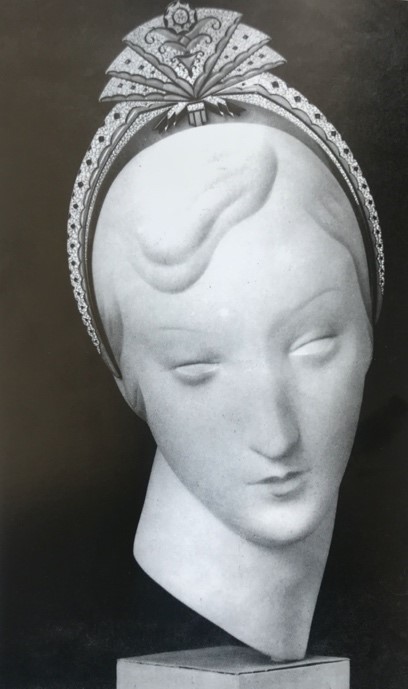

It was in the 1925 Exhibition des Arts Decoratifs that Mauboussin shifted gears. The iconic jewels that Mauboussin displayed brought accolades including a Grand Prix (fig. 6). In the list of those credited for Mauboussin jewels. Interestingly, there is no mention of Georges, but rather three collaborators Pierre, Marcel Goulet and the designer Maurice Vellay. As was common practice in the trade at the time, Mauboussin employed a talented freelance designer to execute their designs (another example was Dusausoy’s 1925 award winning bracelet which was designed by the young freelancer Madeleine Chazel). Valley who, the year previous had won first prize in the Syndicale de Bijouterie de la Joaillerie et de l’Orfevrerie competition in 1924 with a design for a diadem (fig. 7), went on to work as an inhouse designer for a large workshop and his designs were retailed by Lacloche, Tiffany and Ostertag amongst other well-known houses in the 1920s. He also designed textiles and other decorative arts. Valley’s relationship with Mauboussin continued until 1938, or at the very least his design legacy – as can be seen in the diadem Mauboussin exhibited in Athens in 1928 (fig. 8), which is reminiscent of Valley’s 1924 award winning design.

Source: Mauboussin Archives

Around the time of the 1925 Exposition des Arts Decoratifs Pierre was given the task of overseeing the design department at Mauboussin – a role he maintained into the 1930s. Although he wasn’t the one who created the final designs, he seems to have been actively involved in the process. Most directly in the choice of designers to work for the firm, which allowed Pierre to dictate and curate the aesthetic identity of the firm. He also may have done quick sketches for the initial ideas and defining what he wanted. Without a doubt it is from this point one can trace the influence of his other great love: aeroplanes and cars. Unlike his contemporaries, Gerard Sandoz and Jean Fouquet, who nurtured their passions and interests outside their work in the family business (for example Fouquet’s writing – he penned several detective novels and Sandoz’s painting, film making and graphic design), Pierre was allowed, and encouraged, to work on the jewellery business and his aeronautical business in tandem. Through much of the 1920s and early 30s he managed to nurture both, side by side, before fully committing to his airplane business on the eve of World War 2. His interests and his character, without a doubt, informed the identity of Mauboussin and the nature of the house’s output.

Around the time of the 1925 Exposition des Arts Decoratifs Pierre was given the task of overseeing the design department at Mauboussin – a role he maintained into the 1930s. Although he wasn’t the one who created the final designs, he seems to have been actively involved in the process. Most directly in the choice of designers to work for the firm, which allowed Pierre to dictate and curate the aesthetic identity of the firm. He also may have done quick sketches for the initial ideas and defining what he wanted. Without a doubt it is from this point one can trace the influence of his other great love: aeroplanes and cars. Unlike his contemporaries, Gerard Sandoz and Jean Fouquet, who nurtured their passions and interests outside their work in the family business (for example Fouquet’s writing – he penned several detective novels and Sandoz’s painting, film making and graphic design), Pierre was allowed, and encouraged, to work on the jewellery business and his aeronautical business in tandem. Through much of the 1920s and early 30s he managed to nurture both, side by side, before fully committing to his airplane business on the eve of World War 2. His interests and his character, without a doubt, informed the identity of Mauboussin and the nature of the house’s output.

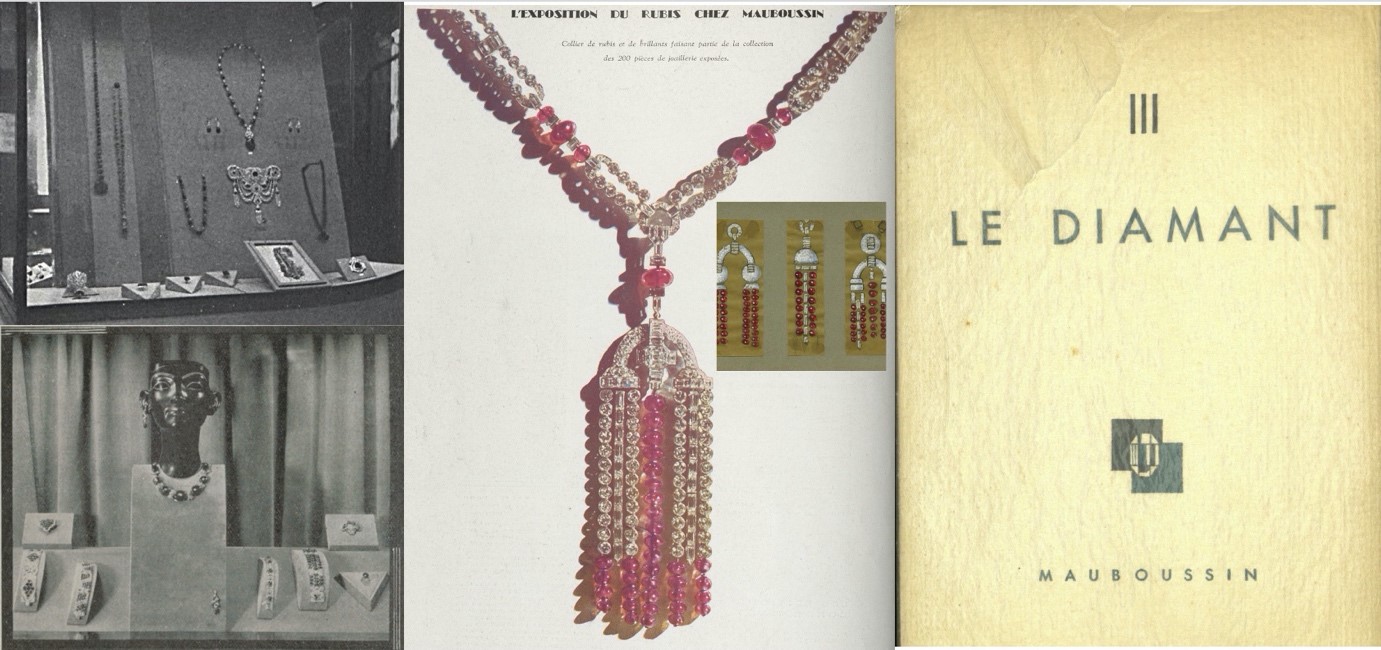

In the years 1926-1931 for Mauboussin and in particular Pierre, were hugely successful and extremely busy. The first trace of his engineering projects is in 1926 when Pierre registered his first patent for a wing device. In 1927 he registered, with a partner, a patent for a clutch control device for cars. Mauboussin as a firm regularly exhibited, along with contemporaries such as Cartier, Dusausoy and Van Cleef & Arpels at the various International and French exhibitions across the globe, promoting French luxury goods. 1928 was a particularly important year for the firm and for Pierre and exemplifies more than anything the diversity and dynamism of Pierre. It was the year of Mauboussin’s Emerald selling exhibition, the first of three exhibitions (fig. 9) that Mauboussin was to hold to critical and commercial acclaim and was followed two further exhibitions: ruby (1930) and diamond (1931). It is hard to tell who instigated the concept of exhibitions at Mauboussin (Goulet, Georges or Pierre) but Pierre embraced it fully and while Georges was the face of the firm, Pierre was often the voice of the firm in the press coverage and interviews.

Fig. 10 Profile of the PM X 1928

Fig. 11 From Left: Pierre Mauboussin (in hat), Charles Fauvel (the pilot) and Peyret (moustache). In front of the PM X c.1928.

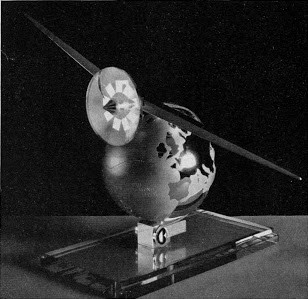

1928 was also the year that Pierre produced his first aeroplane. It was designed and constructed in collaboration with Louis Peyret former head of design the airplane manufacturer Morane Saulnier during the First World War. Rather than target competition aircraft (those that undertook land-speed records and circumnavigated the globe with the intention of breaking records) Pierre targeted the growing field of tourism aviation, creating airplanes for non-commercial pilots. Planes were inexpensive, economical to run, and also able to effortlessly cover distances. The first plane (fig. 10) was the PMX (their planes were classed “PM” and are known as Peyret-Mauboussin”) which set several records in 1929: For altitude, speed over 100 km, distance in closed circuit and in a straight line distance. A modification (the PMXI) equipped with an additional tank was to break the record for distance, covering 1258 km in 12 hours and 3 minutes in 1930 and break further records in 1931 (fig. 11).

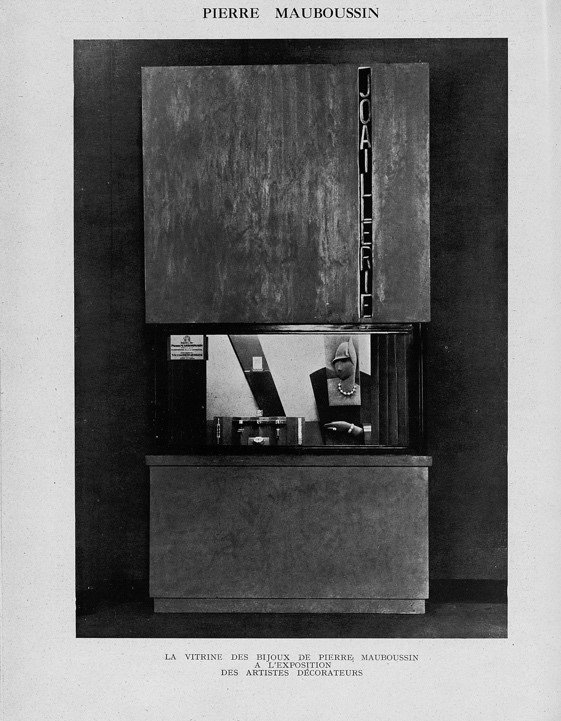

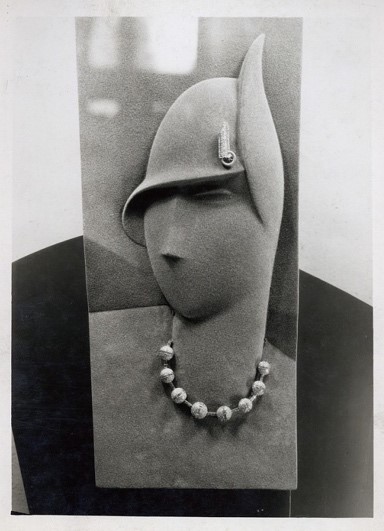

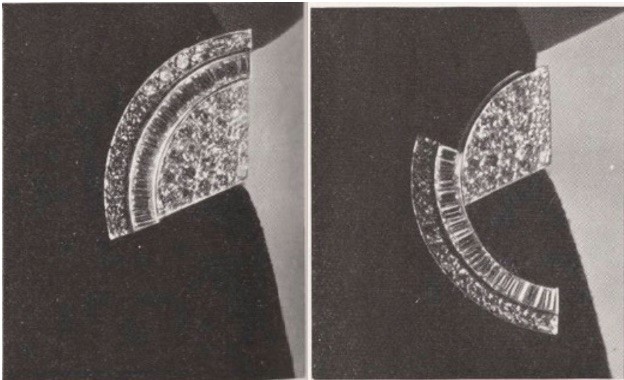

In 1928-29 he worked on another modification of the PMX – a seaplane called the PMXH, which was to break distance records in 1930. It was very much on Pierre’s mind as he had the firm produce a diamond-set miniature of the plane, in brooch form, was exhibited in 1928 at the Salon Des Artistes Decorateurs (SAD). From 1927 onwards, Mauboussin – probably a decision made by Pierre – began to exhibit at the Salon Des Artistes Decorateurs. Notably, under his own name and not Mauboussin’s. His 1927 display was well received, but it was his 1928 exhibition that brought great acclaim (fig. 12). Exhibited alongside with the seaplane brooch and one other nod to his aeronautical interests – the wheel and wing hat brooch, was the star of the show and one of the more iconic jewels (they produced a few) by Mauboussin in the 1920s: a platinum and diamond ‘Sphere’ necklace, bracelet and matching ring. This suite of jewels, designed by draftsman Marcel Mercier, featured spheres set with round brilliant-cut diamonds and divided by a band of baguette-cuts (fig. 13). Although much has been discussed about this design, little has been written about how it was received in a broader context which is worthy of note as it gives an understanding of the unusual breadth of Mauboussin’s scope.

Fig. 12 An image of Pierre’s stand at the 1928 Salon Des Artistes Decorateurs from ‘La Renaissance de l’art français et des industries de luxe’

Fig. 13 Close-up of the ‘Sphere’ necklace exhibited by Pierre Mauboussin in 1928. In the mannequin’s hat is the ‘Wheel and Wing’ hat brooch

Photo: Therese Bonney

The SAD exhibitions, in terms of jewellery we usually the purvey of the jewellers and silversmiths who held a fascination with the machine age and subscribed aesthetically, technically and philosophically to the Modernist doctrines such as Adolf Loos’ 1908 essay ‘Ornament and Crime’ and Le Corbusier’s ‘The Decorative Art of Today (1925) – both of which railed against ornamentation. Pierre Mauboussin, and in turn the firm Mauboussin, was the only one of the large jewellery firms, that exhibited at SAD and the more commercially minded international exhibitions. Moreover, they did so with great success. For Pierre Mauboussin, and his designers, were not only au fait with the Modernist doctrines, technical and philosophical ideals but also prevalent artistic influences such as Cubism, abstraction and later Surrealism. This resulted in jewels that greatly appealed to critics, commentators and arbiters of taste who published their views in the pages of art and design journals of the period. Magazines that otherwise championed the modernist jewellers. These publications include L’amor de l’art, L’Art Vivant and Les Echos des industries d’art to name but a few. Whereas the Modernists created flat, streamlined jewels Pierre gravitated to more sculptural forms. His references to machines and his experiences as an engineer were at times literal (the seaplane brooch) but more often they were subtle and can be seen in the complex patterns of the stone setting. Unlike the Modernists, his jewels were also extremely commercially viable, appealing to a broad client base and Mauboussin’s jewels graced endless pages of the fashion journals of the period – publications that rarely gave column inches to the Modernists. It is worth noting that from 1928 Mauboussin seems to have made a concerted effort to maintain these separate identities. A ruby and diamond brooch (fig. 14) that was displayed in the 1930 Ruby exhibition was attributed to Mauboussin in fashion journals, and to Pierre Mauboussin in the decorative arts journals in which it appeared.

The 1928 ‘Sphere’ jewels appeared on pages of both the fashion and decorative arts periodicals. Fashion journal Fémina devoted a whole page to the designs. There was also a poem penned by the poet Francis de Miomondre in the journal L’Europe Nouvelle in 1928 which was an ode to Pierre Mauboussin and his necklace.

“The modern woman got rid of everything: her high heels, her prejudices, her big hats, her underwear, her long dresses and her hair…

Everything

But her necklace.

Ouch!…

And that’s how we grab her back, that little slave.

And while we’re at it, let’s make this necklace beautiful! and with spheres! and by Pierre Mauboussin!

And nothing prevents her from escaping… with it.”

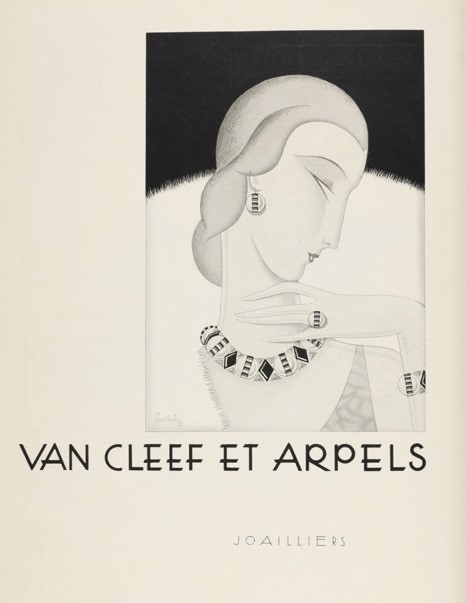

Mauboussin continued to use this seemingly simple motif. They produced at least one other necklace, which now forms part of Neil Lane’s collection and which was exhibited at the Cooper Hewitt in 2017. The motif appears again in the following years: adapted in designs by Van Cleef & Arpels (fig. 15) in an advertisement from 1931 and Mauboussin used it again, probably many times, for example in 1934 it appeared as a modern take on a tiara (fig. 16).

Fig. 15 Van Cleef & Arpels advert from 1931 featuring jewels inspired by Pierre Mauboussin’s ‘Sphere’ suite

Fig. 16 A modern take on a tiara by Mauboussin from 1934 in which the sphere motif is used

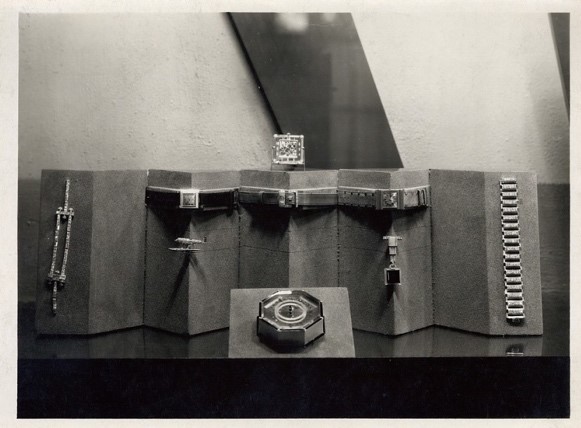

Fig. 17 Close-up of the watches and PMXH seaplane brooch exhibited by Pierre Mauboussin in 1928

Photo: Therese Bonney

Fig. 18 Helene Bouchere atop a Mauboussin plane (M120 Corsaire)

Photo: François Kollar

Fig. 19 A sketch of Mauboussin, wearing his ubiquitous hat, watching Boucher climb into his Corsaire. The drawing dates from 1935 and is from an article discussing her after her death a year before.

Fig. 20 Maryse Hilsz posing in front of the Mauboussin plane she piloted in 1935.

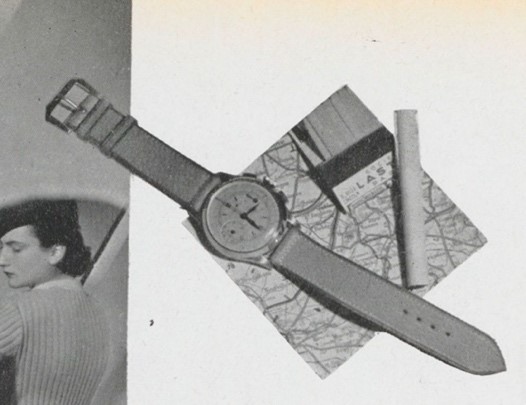

One last thing from that 1928 SAD vitrine that is worth mentioning. The inclusion of watches for both men and women, including a belt watch for women (fig 17). Mauboussin, during this period began to produce watches, not simply gem encrusted dress watches but gold and white metal watches, which formed part of the exhibition displays. In their pricelist for the 1930 ruby exhibition Mauboussin said the following:

“Watches. – To this marvel of the art of watchmaking, the jeweller gives a new meaning. He now turns it into a pin-clip that attaches to the edge of the sleeve, a staple in the skilful fold of a drape; she is also the beating heart of a bracelet; it’s still the bag watch, tiny – and so flat! Finally, a clock, it is a lovely and precious trinket.”

Watches were in part a nod to the growing fashion for watches, but also a reflection of Pierre Mauboussin’s understanding of the accessories that appealed to the modern woman, of which he had an innate understanding. As testament to this relationship with women, during the late 1920’s and 1930s he entrusted celebrated aviatrix to pilot his planes in competition. His successful [professional] relationship with these women is well documented. In 1933 Helene Boucher (fig. 18 & 19) set an altitude and in 1935 Maryse Hilz (fig. 20) set a women’s altitude record in his planes. The Aviatrix in the 1920s and 30s, exemplified by Emelia Earhart, had become one of the ultimate symbols of the modern woman.

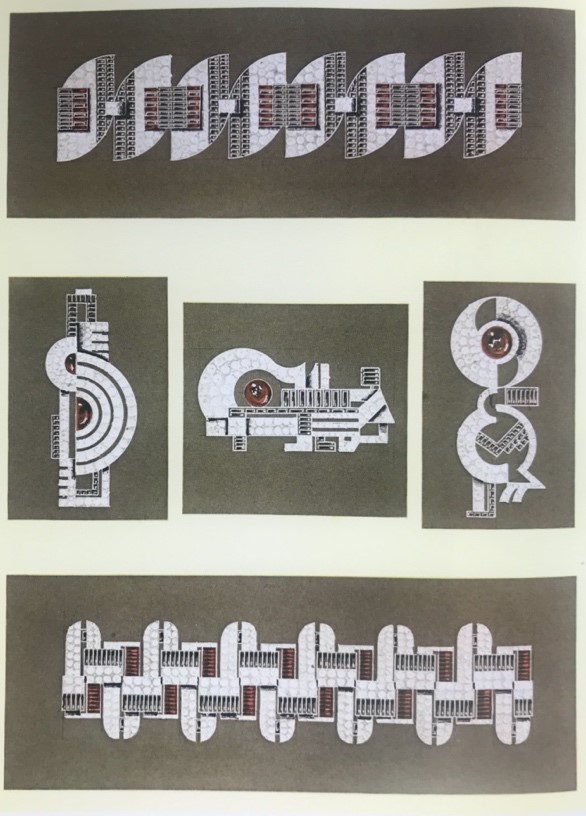

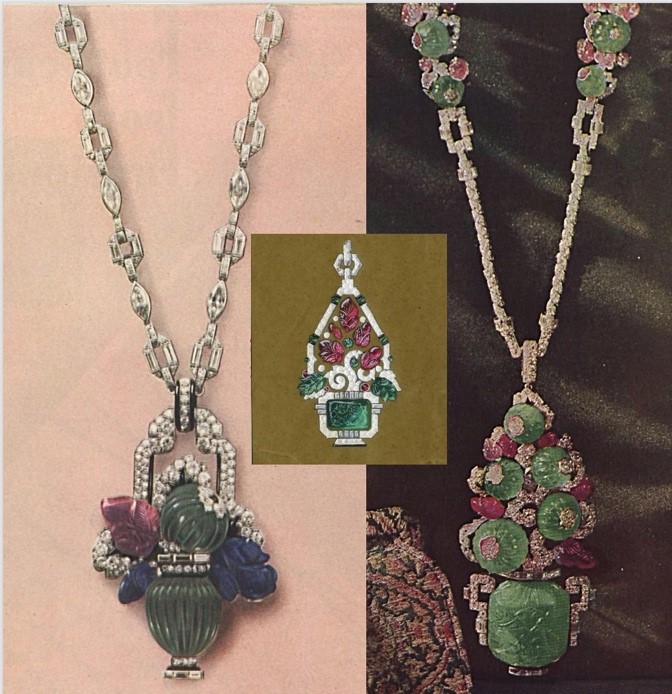

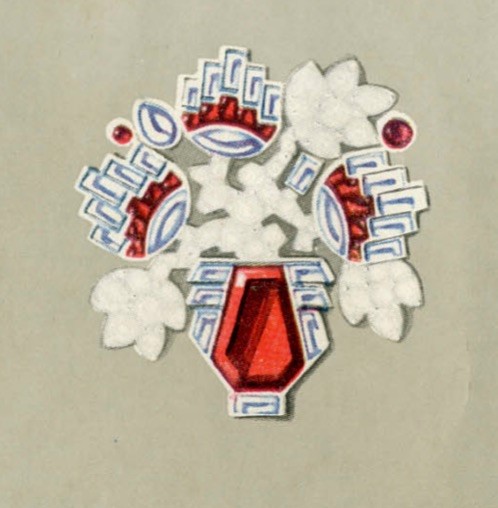

Pierre continued to exhibit successfully at the SAD until the early 1930s (fig. 21 & 22). And in addition to their celebrated emerald, ruby and diamond exhibits, Mauboussin exhibited, to much acclaim, at the 1929 Les Arts de la bijouterie, de la joaillerie et l’orfèvrerie exhibition at the Paris Musée Galliera and the 1931 Exposition Coloniale Internationale in Paris. In both these seminal exhibitions Pierre was recorded as the designer, though in truth he no doubt worked with draughtsmen/draughtswomen employed by the firm on these jewels. In these exhibitions, he continued to focus on the clean minimal lines that so appealed to him, featuring trademark intricate patterns with baguette-cuts that were prominent in the jewels the firm exhibited in the 1929 show at the Musée Galliera (fig. 23). He also began to play with abstract forms, such as a piano brooch, punctuated with a small cabochon ruby. This abstraction was to be further elaborated on at the Ruby Exhibition with a series of other designs relating to the piano brooch (fig. 24). He also began to include coloured stones such as sapphires and emeralds and carved coloured stones which were a nod to the substantial, and hugely successful, ‘Jardinière’ jewels that were laden with coloured carved stones that Mauboussin produced in number during that period. (fig 25). He also designed a modernist ruby and diamond take on a ‘Jardinière’ brooch for the 1929 exhibition (fig 26). These jewels serve to illustrate the diverse aesthetic identity of the firm and yet all the jewels remained easily identifiable as Mauboussin.

Fig. 21 Pierre Mauboussin’s stand from the 1929 Salon Des Artistes Decorateurs. Photo: Therese Bonney

Fig. 22 A vitrine from Pierre Mauboussin’s stand at the 1931 Salon Des Artistes Decorateurs.

Fig. 23 A selection of jewels exhibited by Mauboussin in 1929 at the Musée Galliera that appeared in Figaro – Supplement Artistique and Vogue in 1929. The ruby and diamond brooch sits next to the sapphire and diamond necklace.

Fig. 24 A selection of ruby and diamond abstract designs exhibited at the 1930 Ruby Exhibition. In the centre sits the design for the piano brooch. Source: Mauboussin Archives.

Fig. 25 A pair of Jardinière pendant necklaces by Mauboussin from 1929 that appeared in Vogue. In the centre is a gouache of another design. Source for gouache: Mauboussin Archives.

Fig. 26 A modern take on the Jardinière brooch in rubies and diamonds that was exhibited in 1929.

In 1930-31 his, and his designers, began to create complicated jewels set with diamonds and colour stones. Such as the sapphire, diamond and ruby hair ornament and pendant brooch that appeared at the Ruby exhibition (fig. 27). In 1931, Le Bulletin de l’art ancien et moderne wrote about these jewels:

“Mr. Pierre Mauboussin has produced works whose colourful complication sometimes asserts itself at the expense of form. Its jewels nonetheless retain, by the pleasure of their tonal relationships and the ingenuity of their arrangements, a certain seduction.

Fig. 28 The 1931 rose brooch. Clockwise from bottom left: a schematic design for the brooch, a contemporary photograph of the brooch, An illustration by Charles Martin the brooch and other jewels exhibited at the Exposition Coloniale from a 1931 issue of Harper’s Bazaar.

Fig. 29 A selection of diamond platinum brooches and hair ornaments, some of which include enamel, by Mauboussin dating from 1931-35. They appeared in both art journals and fashion magazines.

In Pierre’s jewels one can also see reference to the artistic developments of the time, biomorphic abstraction, organic surrealism and collage to name but a few. The motifs became increasingly stylised and the jewels began to employ layering through the use of metals, enamel and stone setting to create jewels that were like no other being produced. One of the most striking examples of this is a rose brooch that Mauboussin exhibited at the 1930 SAD, the 1931 Diamond exhibition as well as the 1931 Exposition Coloniale Internationale in Paris. The original design for the jewel (fig. 28) gives some sense of the designer’s reference to art movements of the time and the photograph gives a sense of the layering, which gives the impression of a collage. An illustration celebrating the jewels which were exhibited at the Exposition Coloniale Internationale that featured in a 1931 issue of Harper’s Bazaar allows one to see the varied hues of blue enamel that were used. Note the necklace made in the same vein and the gold vanity case mounted with a diamond and ruby motif that references the abstract jewels exhibited in the Ruby exhibition in the previous year. Pierre and his team went on to further develop this stylised and layered technique. In 1931-2 he produced a series of diamond and platinum jewels, some of which featured enamel work (fig 29). Unfortunately, none have appeared on the market in recent years and so the colour palette is hard to ascertain.

From 1935 onwards, following the collapse of Mauboussin’s business in the U.S.A., the retirement of Georges Mauboussin and Marcel Goulet taking the helm of the firm with the help of his son Jean, Pierre Mauboussin gradually withdrew from his involvement. One can still see traces of his influence, from the large scale aeronautical trophies (fig. 30), the production of a ladies chronograph watch (fig. 31) which was inspired by his aviatrix colleagues, and other jewels such as a patriotic charm bracelet themed around all the French Escadrilles retailed on the eve of World War 2 (fig. 32), and more mechanical pieces such as this sliding brooch (fig. 33). At the same time his aeronautical business grew from strength to strength. Still, in 1940 when the French government took control of his aeronautical enterprises as part of the drive for the war effort, Pierre is registered as having his offices at Rue de Choiseul.

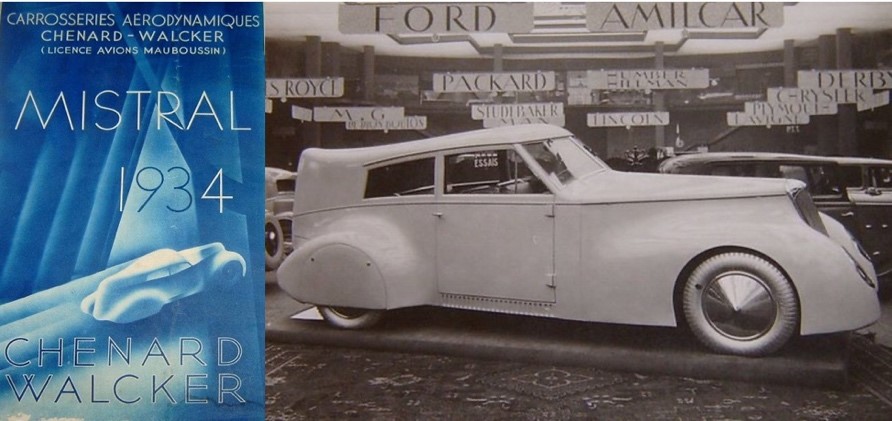

Although this article is about Pierre his design legacy at Mauboussin, it would be remiss to not mention some of his engineering achievements. In 1933 Pierre turned his hand to car design. He believed that the fundamentals he had developed with his planes could apply to a car. The result was the Mistral (fig 34), which was built by Chenard and Walcker and exhibited in 1934. The car proved to be hugely expensive (75,000 francs) and as a consequence few were built and sold, but it generated a huge amount of publicity of Mauboussin and Chenard and Walcker.

Fig. 34 The 1934 Mistral car designed by Pierre Mauboussin and manufactured by Chenard and Walcker

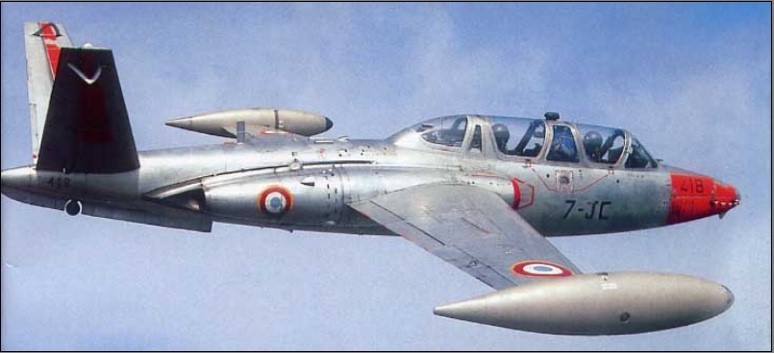

Fig. 35 A Fouga Magister CM 170

Following the death of Louis Peyret in 1933, Mauboussin established his own company and named it Avions Maboussin. Some of the PM models were relabelled M to recognises that they were now Mauboussin planes. During this period he developed a Corsair plane. The M120/32 Corsaire (1932) which was based on his earlier designs. Variants of the M120 were built until 1948 and it remained a popular plane with French flying clubs in the post-war years. In the mid 1930s he approached a woodworking firm by the name of Fouga to manufacture his planes. Fouga, who had traditionally produced rolling stock (railways) saw the benefit in shifting into aeronautical production and by 1936 they bought Avions Mauboussin and all of Mauboussin’s designs. At Fouga, Mauboussin worked alongside another engineer by the name of Robert Castello, and both men played a leading role in the firm. As a result, Fouga’s planes were designated CM in reference to the Castell-Mauboussin team. Fouga focused on military aircraft, initially assault gliders such as the CM 10, but after the war they focused on jet propulsion energy. One of their most lasting legacies was the CM Magister (fig.35), first developed in 1948, which was used by the French, Belgian, Israeli, German and Finnish air force in conflicts and later used for military aeronautical displays. They remained in use until the 1990s. Mauboussin went on to run Fouga until 1967, at which point he retired. His contribution to aeronautical engineering was profound and long lasting and as a consequence he was awarded the Chevalier de la Legion D’honneur and the prestigious La médaille de l’Aéronautique for his services to the field. Pierre left behind no children, although he married (twice) these marriages were later in life. He died in the Oisne in 1984 While his passing did not dim the memory of his contributions to the evolution of aeronautical engineering and design, the same fate did not befall his jewellery legacy – much like the innovative jewels he was responsible for, it is largely forgotten through the vagaries of time, more’s the pity.