Written by Olivier Bachet

Tortoiseshell

Fan, Cartier-Paris, circa 1900

Platinum, diamonds, ostrich feathers and tortoiseshell (Courtesy of Palais Royal)

Opera glasses, Cartier-Paris, circa 1910

Gold agate, diamonds and tortoiseshell (Courtesy of Palais Royal)

Tortoiseshell comes from the backs of tortoises. Translucent, amber in colour, spotted with brown or red markings, or pale yellow with brown or black marbling depending on the species, it was regularly used by Cartier. At the beginning of the XXth century, a multitude of merchants supplied the jeweller with raw material. Amongst them Chatenet and Latouche not far from rue de la Paix, Prével, MacPherson & Billy, both established on rue de Turbigo supplied combs, fans, lorgnette handles, knitting hook tips, fountain pen sleeves, mirrors and a variety of other elements. Tortoiseshell’s easy malleability when heated allowed goldsmiths to use it to cover objects with uneven surfaces.

Writing set, Cartier-Paris, circa 1905

Silver-gilt, enamel and tortoiseshell

This set was purchased in the rue de la paix store by the diva Nelly Melba in April 1905 (Courtesy of Palais Royal)

Cigarette holder, Cartier, 1928

Gold, platinum, jet, diamonds, emerald and tortoiseshell (Courtesy of Palais Royal)

Hair comb, Cartier-Palais, circa 1925

Platinum, diamonds, black enamel and tortoiseshell (Courtesy of Palais Royal)

Gold, enamel, emerald and tortoiseshell (Courtesy of Palais Royal)

A pair of gold opera glasses were thus covered with a beautiful transparent blond tortoiseshell which meant that the gold’s guilloché aspect could be seen, giving it the appearance of orange enamel (see illustration). To accentuate the preciousness of these objects made with tortoiseshell, small gold dots were inlaid into the surface using the “piqué” technique. Very fashionable in the XVIIIth century, this technique meant that the goldsmith drew the desired pattern on the tortoiseshell and then after piercing the required spaces, he heated the tortoiseshell to enlarge the hole in which he was to place the gold decor. The eventual cooling down of the tortoiseshell imprisoned the gold motif definitively. During the period between the two Wars, large pieces made in tortoiseshell were gradually abandoned. Although a few desk clocks with folding struts and some simple table cigarette boxes were made, its main use was for combs and for the backs of mirrors for vanity cases. Although blond tortoiseshell was mostly used at Cartier, the brown tortoiseshell was also used for some elements as for the comb illustrated here. With the 1929 economic crisis, the workmanship required, as well as the material’s price, meant that its use was gradually abandoned, to be replaced with synthetic substances such as celluloid and Bakelite.

Some desk clocks were also covered in lacquer imitating tortoiseshell such as a model in the shape of a sea mine, registered for Paris stock on 11th December, 1930 and described in the archives as “a spherical clock in tortoiseshell lacquer.” After the Second World War, its use remained about the same as before and other than for a small desk clock by Cartier-London whereby the dial was made using brown tortoiseshell, it was no longer used to make important pieces, as had been the case at the beginning of the century.

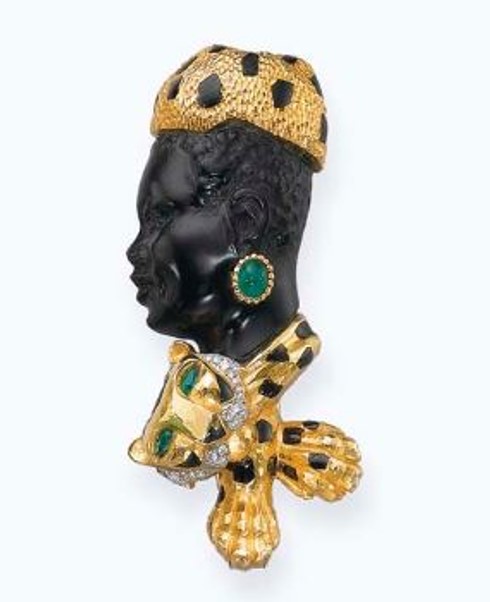

As far as jewellery is concerned, the use of tortoiseshell developed particularly in the 1960s with a series of jewels that met with great success: the Blackamoor clips. Representing proud African warriors, these clips, which appear in the shape of a gold bust often adorned with precious stones and a head engraved in brown tortoiseshell, have become icons of jewellery (see Illustration).

Like ivory and for the same reasons related to the protection of wildlife, the use of tortoiseshell in jewellery has now completely disappeared.