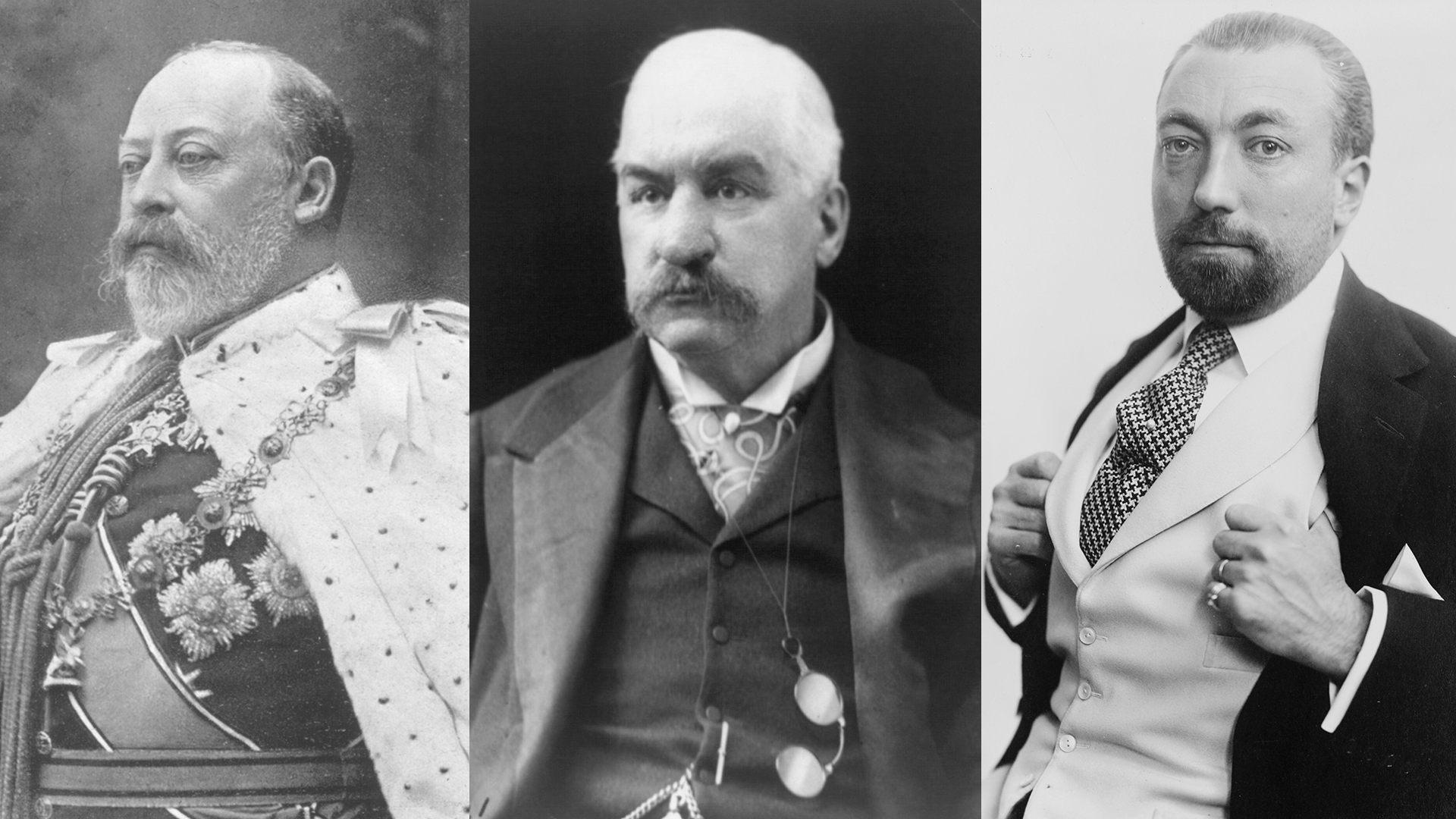

In every industry there is somebody, or perhaps several somebodies, who are not directly involved in that particular business, yet they manage to have an outsize influence. That was the case in the early 20th century when French couturier Paul Poiret, American financier JP Morgan and Britain’s King Edward VII helped shape the worlds of fashion, gemstones and jewelry.

King Edward VII (1841-1910)

King Edward VII was the partying, fun-loving eldest son of Queen Victoria. His influence began while he was still Prince of Wales, when he began taking over social occasions as his mother, lost in mourning for her deceased husband Prince Albert, withdrew from public life.

The King was known to keep a very formal court hosting myriad balls, parties and dinners. It was expected that one would be dressed in formal wear and that included jewelry, especially tiaras. That expectation was so firmly entrenched, that King Edward once allegedly scolded the Duchess of Marlborough for showing up at an event with a diamond brooch in her hair rather than a tiara. According to an entry in her diary, she was forced to explain that she had been doing charity work and hadn’t been able to get to the bank to retrieve her tiara before it closed.

In 1902, Cartier opened its first London branch. Cartier was a favorite of the king who proclaimed that Cartier was “The jeweler of Kings and the King of jewelers.” In 1904 the company was honored with the first of fifteen royal warrants appointing Cartier as the official purveyor to the court of King Edward VII.

On November 9, 1907, King Edward was gifted the ultimate birthday present: The Cullinan diamond. It was given to him by the Transvaal government (a province in South Africa) as a 66th birthday gift to mend relations between the two countries that had become frayed during the second Boer war. After being presented to King Edward in a ceremony at the Palace, the stone was eventually cut by the Asscher Diamond Company in Amsterdam and some of the resulting gems are now part of the Crown Jewels, or part of the British royals private collection.

JP Morgan (1837 – 1913)

Best known as a financier, John Pierpont (JP) Morgan, was instrumental in the start-up of the General Electric Company and the U.S. Steel Corp., among other businesses, he was also a collector of rare books, art and gemstones. He was a founding member of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City and was on its board of trustees from its opening in 1869 until his death in 1913.

A deep interest in gemstones led Morgan to befriend George Frederick Kunz, Tiffany & Co.’s first gemologist. Together the duo put together two of the world’s best known gem collections. The first collection “Gems and Precious Stones from North America”, which featured over 1,000 gems, was displayed at the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris where it was awarded two medals. Morgan commissioned Kunz to travel the world locating and buying the best examples of various gemstones in 1900. This second compilation of gems was named the Tiffany-Morgan collection. The two collections were donated to the American Museum of Natural History by Morgan. Together the collections totaled 2,176 gemstones and 2,442 pearls.

Morgan was acknowledged for his contributions to the world of gemstones in 1910 when a new form of pink beryl was discovered in California near San Diego. Kunz was greatly interested in this pink beryl, which needed a name. When showing it to the members of the New York Academy of Sciences, Kunz suggested that the stone be named Morganite to honor JP Morgan. The academy agreed and today this lovely peachy-pink stone is a reminder of the many ways JP Morgan helped to bring knowledge and appreciation of the mineral world to the public.

Paul Poiret (1879 – 1944)

Paul Poiret was a French couturier who changed the way that women dressed in the first two decades of the 20th century. It also happened that his sister, Jeanne, was married to the acclaimed jewelry designer Rene Boivin.

Poiret got his start in the fashion world working in an umbrella factory, where he collected discarded scraps, turning them into doll clothes. He also began sketching designs and selling them to other established designers before being hired by Jacques Doucet a renowned apparel designer. In 1901 Poiret joined the house of Worth, leaving two years later to start his own firm after a disastrous encounter with a Princess who dissed his designs.

Poiret was one of the first designers to free women from undergarments that changed the shape of their figure. He first got rid of petticoats in 1903, which reduced the size of the voluminous skirts from previous years. Then he got rid of the corset in 1906. This created another major change in the shape of a woman’s figure, allowing Poiret to design looser, tubular clothes that were easier to wear at a time when women were becoming more active. These changes also impacted clothing construction moving from tailoring to draping.

Poiret’s clothes were influenced by The Tales of the Arabian Nights and Ballets Russes, both of which were rich in Asian influences, in terms of style and in the use of color. He used a bold color palette in new combinations with his pared down silhouettes. The impact on jewelry was notable. The garland styles of the Edwardian era began shifting to sleeker more geometric styles, necklaces became longer and swingier to complement the ease of the new styles. Color gemstones in jewelry also began to replace the formal white-on-white look. It must also be noted that Poiret held extravagant parties to promote his clothes attended by his sister Jeanne and her husband Rene Boivin, which notably helped the couple build their own wealthy clientele that furthered their jewelry business.

Top of page: King Edward VII of England, 1901, photograph by William Edward Downey, Public Domain, WikiCommons; JP Morgan, 1915, Public Domain, courtesy WikiCommons; Paul Poiret, 1913, public domain, courtesy WikiCommons.

Authored by Amber Michelle