From a very young age, George Frederick Kunz, was fascinated by minerals and rocks, a passion that he parlayed into a notable career that saw his expertise recognized by Tiffany & Co. as well as the U.S. Geological Survey. Although he was a student at Cooper Union in New York City, Kunz didn’t graduate and was a self-taught mineralogist, with a particular fondness for meteorites. He was an avid author who was awarded honorary degrees, from Cooper union, Columbia University and Knox College in Illinois, despite never finishing college, or having any kind of formal training. With all of his accolades and accomplishments, Kunz was still best known for being the gem expert at Tiffany & Co. from 1879 until his death in 1932.

Kunz Starts Collecting

As a young child, Kunz, who was born in Manhattan in 1856, was a rock and mineral collector, often finding his treasures at construction sites for bridges and railroads. By the time he was a teenager, Kunz had built a mineral collection comprised of some 4,000 specimens. He sold the collection to the University of Minnesota for $400, selling it not so much for the money, but because he wanted to be recognized as a serious mineral collector.

Determined to share his love of gems with others, in 1875, when he was just 19-years old, Kunz approached Tiffany & Co. with an uncut tourmaline that he was selling. It was a tough sell because the retailer focused on diamonds, rubies, sapphires and emeralds. However, the firm took a chance by cutting the stone and setting it in jewelry. Much to the surprise of those involved (except maybe Kunz) the jewelry sold well.

In 1879, when he was 23-years old, Kunz was hired to be the “gem expert” at Tiffany & Co. The term gemologist was not yet in use, and became part of jewelry vocabulary shortly after his death in 1932. His first task after he was hired by Tiffany & Co., was to supervise the design and cutting of a 287.42-carat rough yellow diamond from the renowned Kimberley Mine in South Africa. The rock had been discovered in 1877 and Charles Lewis Tiffany purchased it in Paris a year later for $18,000. Kunz and his associates studied the rough diamond for about a year, before the cutting process began. Named the Tiffany Diamond, the gem was transformed into a 128.54-carat cushion-cut diamond with 82 facets, 24 more than the usual 56, giving it spectacular sparkle and depth of color. It is currently on permanent display at the Tiffany & Co. store in New York City.

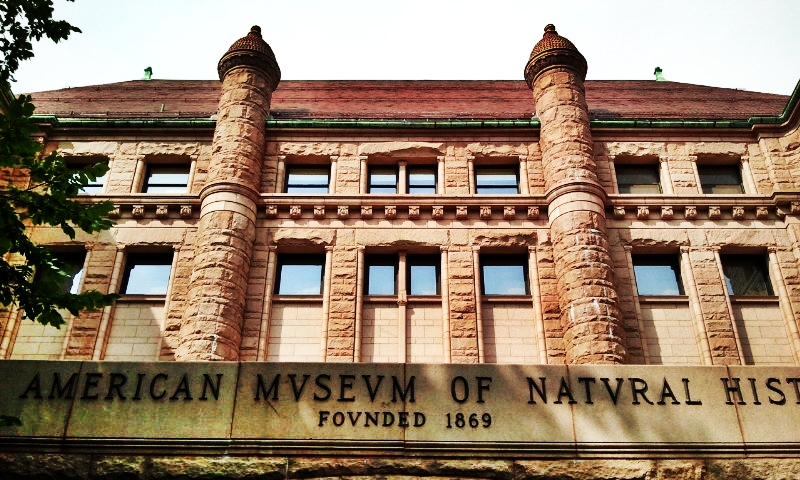

Kunz, JP Morgan and the American Museum of Natural History

Through his work at Tiffany & Co., Kunz met financier John Pierpont (JP) Morgan, who also had an ardent interest in gemstones and mineralogy. Morgan commissioned Kunz to develop a gemstone collection to be presented at the 1889 Exposition Universelle, Paris. The 382 piece collection was awarded two gold medals. A few years later, in 1900, Morgan approached Kunz to develop a world-class collection of gems, that included acquiring an assemblage of 12,300 pieces from Philadelphia-based industrialist Clarence S. Bement as part of the collection. The collection was donated to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, where it can be seen today. Among the many projects he had going on, Kunz was also a research curator for the museum.

Kunz and Colored Gemstones

When Kunz was hired at Tiffany & Co., part of his job description was to bring more colored gemstones to the public. Due to his reputation as a gem expert, miners and jewelers often sent him packages of stones to identify. This provided a unique opportunity for discovering new gemstones and launching them into the marketplace. One day Kunz received a package from Montana. When opened it revealed some bright blue gems that turned out to be sapphires, from the Yogo Gulch, which has become an important source of the gems in the U.S. and still produces stones today.

In another instance, some miners from California sent Kunz a specimen of a mineral they found, but due to its pinkish-purple color, they were unable to identify it. Kunz examined the sample and determined that it was the mineral spodumene in a newly discovered color. Members of the New York Science Academy named the stone kunzite in honor of Kunz. In 1910, Kunz identified a new pinkish-peach stone from Madagascar as a form of beryl. We know it today as Morganite, named for JP Morgan due to his contributions to the world of mineralogy.

While stones were sometimes sent to Kunz, he also traveled to locations known for unique gemstones, including a trip to the Ural mountains in Russia funded by Tiffany & Co. and JP Morgan to locate sources of colored gemstones. He returned with demantoid garnets and alexandrite, both of which were used in Tiffany & Co. designs.

Kunz was active in a number of mineral clubs and associations and he was a cofounder of the New York Mineralogical Club, which still exists today as the oldest continuously operating mineralogical club in the U.S. He was also in charge of U.S. mining and mineralogical exhibits at international expositions, twice in Paris as well as in Chicago, Atlanta and St. Louis. In addition, Kunz was a leading voice in establishing the carat as a unit of measurement for gems.

Kunz Was a Prolific Writer

During his lifetime, Kunz authored over 300 articles and numerous books. One of his definitive works was written in 1883, “American Gems and Precious Stones”, which was a report for the annual United States Geological Survey’s “Mineral Resources of the United States”. He was also a special agent for the US Geological Survey from 1883 until 1909 and for the next fifty years, his reports appeared regularly in the publication. His first book “Gems and Precious Stones of North America” was published in 1890. Some of his books can still be found in print today.

One of his most famous writings was a pamphlet for Tiffany & Co. “Natal Stones: Sentiments and Superstitions Connected with Precious Stones”, which tracked the Hindu and biblical origins and meanings of birthstones. First written in 1891, the 15 page pamphlets were given to customers at the store and was a precursor to the birthstone charts that we use today. The text eventually expanded to 40 pages, with the last edition published in 1931.

Kunz also had an extensive personal library of several thousand books about gems that included not just the geological attributes of gems, but also the lore, history and metaphysical aspects of gems. When he died in 1932, his book collection was sold to the United States Geological Survey Library a year later for one dollar. The books continue to be an important part of the library’s offerings.

From the Tiffany Diamond, to kunzite and morganite as well as his many books and articles, George Kunz left an indelible mark on the world of gemstones and minerals.

Top of Page: George Frederick Kunz, circa 1900, unknown author, courtesy WikiCommons.

Authored by Amber Michelle