Portrait of Suzanne Belperron and Toi et Moi Virgin Gold ring, all images courtesy Belperron.

Recognized as one of the 20th century’s most influential jewelry designers, Suzanne Belperron remains a bit of an enigma. Fiercely private, almost secretive, her talent was undeniable. Despite being conceived many decades ago, part of the genius of Belperron is that her work looks as contemporary today as when it was first produced.

“She was a woman designing for women at a time when jewelry making was dominated by men,” explains Nico Landrigan, president, Belperron. “She mastered many jewelry making techniques and then combined them all.”

Born Madeleine Suzanne Vuillerme in Saint-Claude, France in 1900, her family moved to Besançon a year later. She became Madame Belperron when she married engineer Jean Belperron in 1924.

Her mother recognized Belperron’s talent at a young age and encouraged her to pursue her art. Belperron attended the Besançon Ecole des Beaux Arts. After graduating from school in 1919, Belperron moved to Paris, where she was hired by the Maison Boivin as a model-maker and designer. She never signed her work, but her style was recognizable and it changed the design aesthetic of the firm.

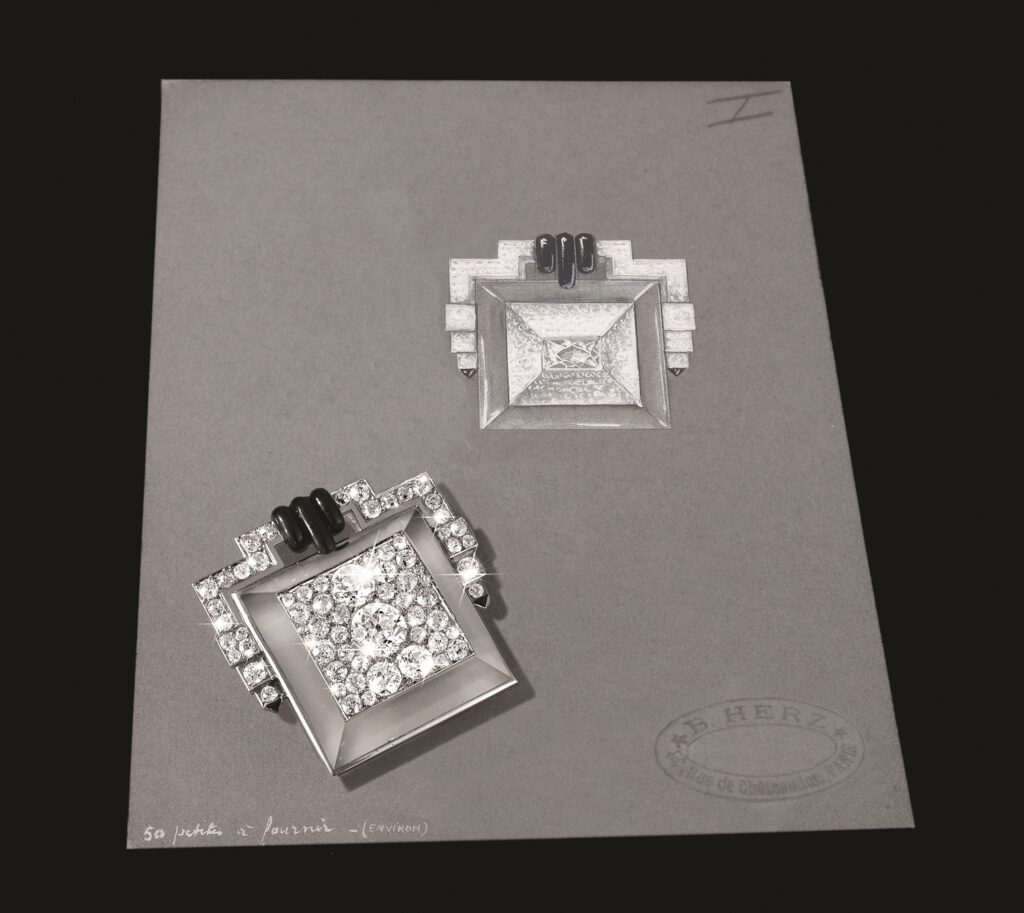

Suzanne Belperron and Bernard Herz

After a few years at Boivin, Belperron was offered a position by Bernard Herz, a high-end gem and pearl dealer. She was hired to design exclusively under his company name, B. Herz, and was given free rein to design as she pleased. Again she declined to sign her creations famously stating that “my style is my signature.”

So how do you know if a piece is by Belperron? She had a very extensive archives of 9,300 sketches and in 2015 Nico Landrigan and his father Ward, relaunched the brand, after acquiring the archives and the Belperron name and trademark in 1998. One of the things that they needed to figure out before the launch was how to distinguish the newly made Belperron from the vintage pieces.

“The new pieces are signed Belperron in bold block letters,” says Landrigan. “Some pieces are rock crystal or hardstone and there is no space for a signature so we put a coded scratch number on the piece. We have a record of all the pieces we’ve made.”

When Belperron left Boivin for B. Herz, she kept the same workshop, Groené et Darde, and the pieces designed by Belperron have those maker marks. According to Landrigan, the French system of marks is very structured and those pieces with the workshop marks help to identity her vintage jewelry. The Belperron archives can also be accessed to verify that a jewel is actually her design.

“The archives are critical to identifying Belperron’s work,” comments Landrigan. “You have to study how a piece is constructed, see the markings, but without the archives, it’s hard to be sure if the pieces are authentic.”

Belperron and World War II

In 1941 when World War II was on Europe’s doorstep, Bernard Herz asked Belperron to purchase the business from him so she could keep it going during the Nazi occupation of Paris. A year later, he was arrested and sent to jail. Belperron was part of the French Resistance and she was able to get him released, but he was arrested again and she was unable to secure his release the second time. He was sent to a concentration camp and did not survive the war.

Despite the difficulty in accessing materials to make jewelry, Belperron kept the business going throughout the war and in 1945, after spending five years in a prison camp, Bernard Herz’s son Jean Herz returned to Paris. Belperron gave the company back to Herz and he made her an equal partner in the business — Jean Herz-Suzanne Belperron, S.A.R.L.

During her career Belperron challenged traditional thinking about what jewelry should look like and how it is made. She created large-scale, curvaceous and voluptuous pieces that are as stylish now as when they were first made.

“She was an exceptional artist,” observes Landrigan. “I think she foresaw a modern style. She looked into the future. She had restraint and balance in her jewelry. She never gave everything away at a first glance. You really have to zoom in and look at her pieces, the more you look the better it gets.”

Belperron and Serti Couteau

Landrigan notes that Belperron invented her own style of setting to accommodate her designs. She liked to create pieces with multiple gemstones in different sizes and shapes, so she developed a special setting, serti couteau, or knife edge, to hold the stones in place. The setting technique, which looks like an irregular honeycomb on the back, became a part of the design. The setting allowed Belperron to mount stones of various shapes and sizes into her pieces in a random pattern. She also pioneered the setting of gemstones into hardstone, a favorite combination was diamonds in rock crystal. Some of her all gold pieces were textured — through the use of microhammering and scratching – to look ancient.

Belperron worked very closely with her clients. She custom made jewels in collaboration with her client, taking meticulous measurements of the fingers and wrists to make sure that the finished jewel was a perfect fit.

In 1963 Belperron was given the Knight of the Legion of Honor award by the French government for her contributions as a jewelry designer. It is the highest distinction given to a French citizen. In 1974, after 55 years in the business, 42 with the Herz family, Belperron and Jean Herz closed up shop and retired. Belperron passed away in Paris in 1983, but her artistic legacy lives on through the jewels she created.

The late great designer Karl Lagerfeld summed up the essence of Belperron’s work when he wrote the forward to the book “The Jewelry of Suzanne Belperron” by Patricia Corbett, Ward Landrigan and Nico Landrigan. “There is a humble splendor you can never find in other designers’ work before her. One feels that the heart always prevailed,” concluded Lagerfeld.

Authored by Amber Michelle