From the Roman ruins to the famed art of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, mosaics have had an important place in art, jewelry and history. Generally, when we think of mosaics we think of the ornate floors, walls and ceilings that were made from this art form in the ancient world. However, mosaics, including micromosaic jewelry, have had lasting power and continue to fascinate art lovers today.

The large scale mosaics of the Roman and Byzantine eras that covered walls and floors were made of stone, pebbles, shell, glass and other available materials. Mosaics were a particularly sturdy and popular artform that lent itself to being scaled down in size for decorative objects such as tables, boxes and plaques. This eventually led to mosaics being scaled down to even smaller sizes for use in jewelry. These microsmosaics were trending in the mid 1800s as tourists flocked to the Continent (Europe) for the Grand Tour (an educational trip around Europe for aristocratic young men with Italy as a key destination) and wanted souvenirs to take home. Micromosaic jewelry, known at the time as Roman Mosaics, was the perfect souvenir.

How are Micromosaics Made?

Microsmosaic jewelry was very popular in the 1700 and 1800s. Made mostly in Italy, it was imported to England and France. So what exactly is micromosaic? A very labor -intensive process, micromosaics are created using teeny bits of glass, or enamel, known as tesserae, which come in many colors. For jewelry use, a precious metal backing is filled with a cement-like glue, then an artisan using tweezers, places the individual tesserae into a pattern until an image is formed. Once the glue has dried, wax is used to fill the spaces between the tesserae and then the entire image is polished to a smooth surface. The micromosaics were often adorned with elaborate settings that were further embellished with enamel, cannetille or other decorative work.

The imagery on micromosaics showed scenes of country life, flowers, animals – dogs in particular as they represented love and fidelity in the Victorian era. Mythology and Egyptian themes were also popular. Egypt was of great interest to people in the late 1700s and early 1800s due to Napoleon Bonaparte’s, Egyptian War that lasted from 1798 to 1801.

Castellani and Raffaelli Pioneered Micromosaics

Forunato Pio Castellani and Giacomo Raffaelli were two important artists in microsmosaic work. Raffaelli who achieved fame for his microsmosaic work, was one of the first to use the technique in jewelry. He also founded the “School of Mosaics” in Milan in 1804. He is well known for his mosaic recreating the Leonardo da Vinci painting “The Last Supper”. It was commissioned by Napoleon I and took eight years to create. It resides in the Minoriten Church in Vienna.

Castellani was a goldsmith in Rome who was very important in the Archeological Revival jewelry movement which drew inspiration from ancient jewels such as Etruscan and Roman era styles. Castellani used Christian-Byzantine, Egyptian and classical Greek motifs in micromosaics. His micromosiac work was also unique in the finishing. Instead of polishing the tesserae into a smooth, even surface, he left the surface a little uneven so that the tesserae could catch the light and sparkle.

These artful jewels had a name change when British decorative arts collector, Sir Arthur Gilbert, decided that calling these jewels Roman Mosaics was misleading as it makes them sound as if they came from the Roman era, which they do not. He came up with the term micromosaic to describe the pieces. His vast collection is now housed in two museums: The Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in California. Today, a handful of artisans continue to create micromosaics.

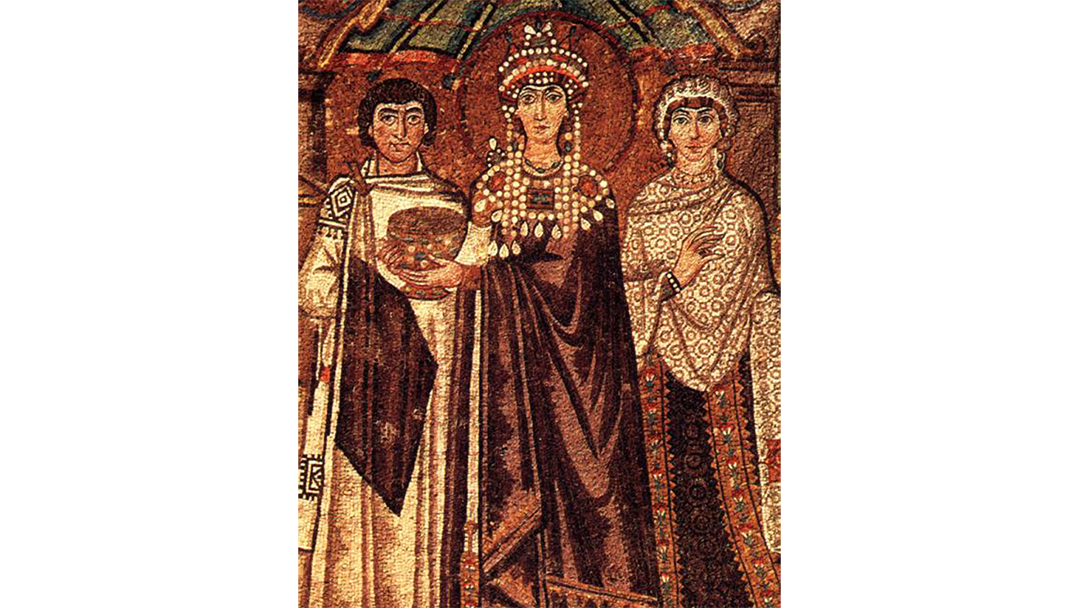

Featured image (top of page): Byzantine mosaic depicting Empress Theodora (6th century) flanked by a chaplain and a court lady believed to be her confidant Antonina, wife of general Belisarius.

Authored by Amber Michelle